De Stationstuinen

Four Ideals in Theory and Practice

In contemporary urban design certain ideals are so pervasive that their meaning has been hollowed out through naive misappropriation, tedious repetition, opportunistic lip-service, malicious manipulation and other abuses.

Themes such as sustainability, participation, inclusiveness and resilience, albeit relevant, are examples of ideals that are hard to embrace without a hint of skepticism. How can we counter the inflationary predicament wherein we become desensitized and cynical about ideals just when they are becoming mainstream? Shouldn’t the goal of every ideal be to become normal? Is the challenge of large ambitions that we get bored of them, before we have even begun to realize them? Or are we in an upward trajectory where we are constantly raising the bar as former goals become commonplace?

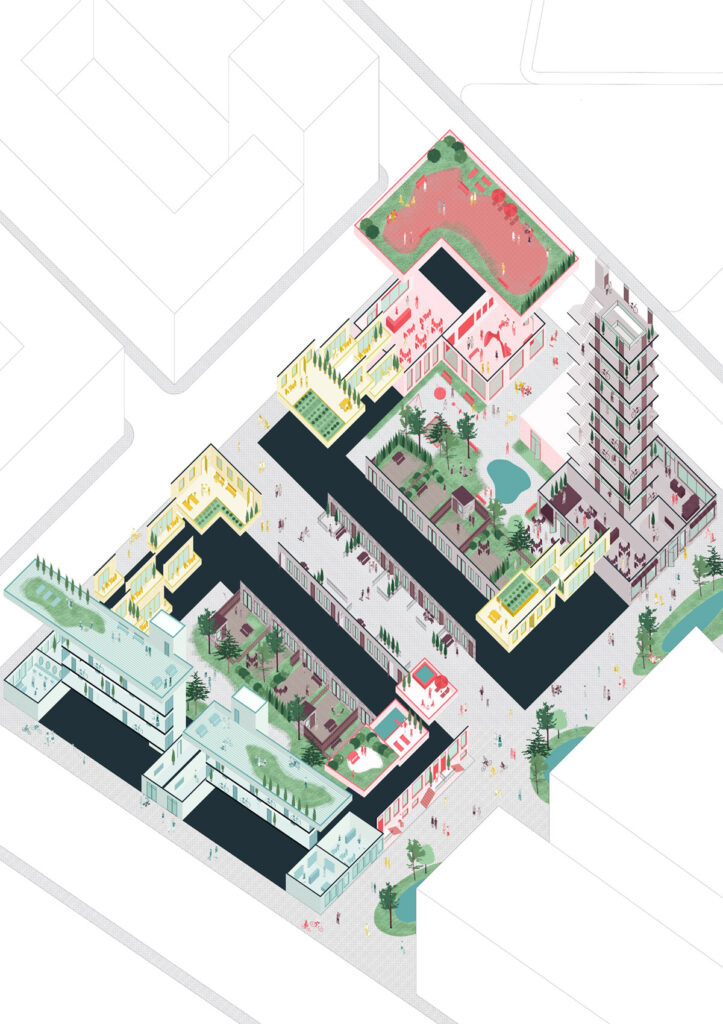

The project “Stationstuinen – Four Ideals in Theory and Practice” was created as part of the 2020 Bouwen aan Talent program initiated by the Dutch Creative Industries Fund. The architectural office Rademacher de Vries Architecten (RDVA) have collaborated with architect and researcher Jana Culek (Studio Fabula) in order to investigate the tensions that occur between contemporary urban design practice and the history of architectural and urban ideals. Based on an ongoing project of RDVA for the design of a new neighbourhood in Barendrecht (NL), “Stationstuinen – Four Ideals in Theory and Practice” investigates the historical, fictional and utopian precedents of four practice-based urban ideals upon which the design of the Barendrecht neighbourhood is based, namely: metropolitan urbanity, inclusive urban form, mobility, and nature as public space. Throughout the collaborative process, the four ideals have been investigated through a two-fold approach which has combined architectural theory and practice, with the aim of tracing the precedents and forming taxonomies of the urban ideals, situating them within the broad field of architectural and urban history. The project brings theory and practice into an active dialogue through identifying a set of key canonical projects (realised or fictional), which could be considered as roots for each of the four ideals.

Metropolitan Urbanity

Metropolitan urbanity is considered as a condition in which a dense and concurrent availability of functions is provided for the inhabitants, that also simultaneously works to differentiate the metropolitan urban area from its non-urban surroundings – the hinterland.

The modern concept of the metropolis has always had an ambiguous meaning. Appearing in its current form the 19th century, it has signified the simultaneous embodiment of the contemporary (post)industrial society and the loss of individuality and community values. With the development of industrial methods of production and the capitalist economic system, the metropolis became the primary habitus for people of all classes, backgrounds and occupations. Rural areas were slowly abandoned in search for better work and life opportunities in the city leading to overcrowding which resulted in bad hygienic and living conditions for the majority of the new metropolitan working population.

The related concept of metropolitanism – or one’s condition of being metropolitan – which appeared simultaneously with the metropolis, was developed as a differentiator of the urban middle class (bourgeoisie) from the previously rural working class. A condition which began as a social and economic divider, soon became an approach to city planning and development, in which the social and economic differences were being physically implemented on the spatial level of the city and its architecture. Through varied distribution of functions and amenities and through radical differences of spatial and living standards, the metropolis which was intended for and housed all, soon became segmented.

With the coming of the Modern Movement which brought with it urban planning approaches such as functional zoning these segmentations and differentiations often became even more pronounced, although the intentions were often quite opposite.

Today, one of the main spatial attributes of the metropolis is still its centrality in relation to its surroundings and its spatial and functional differentiation from the rural hinterland. The metropolis is signified by a high concentration of different functions, amenities, activities and stimuli. Everything one would need or want is available and accessible there. Through investigating both positive and negative aspects of metropolitan legacy, we ask ourselves if the condition of metropolitan urbanity can be employed in order to provide all the positive and productive functions of the metropolis, but perhaps not located only in the metropolis itself. Operating, perhaps, on a different scale than that found in the metropolis itself, the condition of metropolitan urbanity can perhaps also be implemented somewhere closer to its rural hinterland.

Georg Grosz, Metropolis, 1917 / Denise Scott-Brown, Las Vegas, 1956-1966 / Ludwig Meidner, The City and I, 1913

Inclusive Urban Form

Through proposing new architectural and planning approaches in creating inclusive urban forms, we questions the established historical and contemporary methods of distributing housing for people of different economic and social classes.

The majority of our urban history is signified by either a lesser or greater spatial segregation of economic and social classes. Throughout most of history this segregation was related to forms of work and the amounts of people which operated in a specific sector. In times when the majority of the working class was were agricultural workers or manual laborers, it was deemed necessary that they inhabit areas outside of the cities due to the close proximity to their work. With the industrial revolution and the development of mass production, a large portion of the working class is relocated closer to the cities – again in close proximity to their work location, this time the factory. Due to better connections with urban infrastructures, these zones now inhabited areas much closer to the cities, if not even within the urban fabric itself. But even though they were placed within the urban fabric, the segregation according to social and economic class was still visible. Various architects and urban planners from the modernist period address the topic of an egalitarian or inclusive urban form, by acknowledging that both the inhabitants and the ways of working and living in the city have changed.

Throughout the last century, the activities of the working class have changed again, and the locations of their work are now spread out throughout the city and throughout different business and productive sectors. What was perhaps once an excuse for segregation is today no longer valid. How and where we live, regardless of our social and economic status, has become more similar than ever, and because fo that equality and inclusivity should be strived for in all aspects of city life. Is there a way that we can overcome the legacy of functional zoning which separates and delineates and think about different ways of creating spaces and cities in which people from all social and economic backgrounds can enjoy the same benefits the contemporary city has to offer through more inclusive urban forms?

Mobility

The topic of mobility focuses on providing alternative low and zero-carbon options rather than developing car-based infrastructural and mobility networks. By prioritising public transport, vehicle sharing and pedestrians, it counters a long history of automobile focused urban transportation ideals.

The majority of modern urban planning history has devoted part of its focus on addressing the topic of mobility. But since the development and wide use of the personal automobile, this focus has been mostly on creating vast networks of automotive-based infrastructure, often to the detriment of all other urban and rural functions. The car has often been seen as the invention which would allow unobstructed connection between various places and people, and which would allow the individual to independently travel anywhere in a relatively short amount of time.

This approach, or ideal, has unfortunately had an enormous (and often very negative) impact on the appearance of our built environment, and our public and open spaces. While the negative spatial implications of both moving and stationary traffic networks are impossible to miss, the urban obsession with car-based mobility infrastructure has also had a detrimental effect on the overall health of our surroundings.

Looking into alternative mobility options, ones which are not car and carbon based, is a must for both our present and our future. However, the beneficial aspects of automotive infrastructural networks such as ease of connectivity, freedom of movement, and the possibility to live in more remote areas while still having access to contemporary urban amenities are aspects which are often difficult to come by without the existence of said infrastructure. Is there a possibility to utilize other types of transportation networks and systems such as existing rail, road or water based public transport, and achieve the same benefits which were once only attributed the ownership of a personal vehicle? Are there perhaps other systems of use, such as vehicle sharing, which could allow us to at least scale down the size of our current car-based mobility networks? Is it possible to rethink urban centers and allow for optimal mobility and connectivity without using the car at all?

Walt Disney, Magic Highway USA (scenes from film), 1958

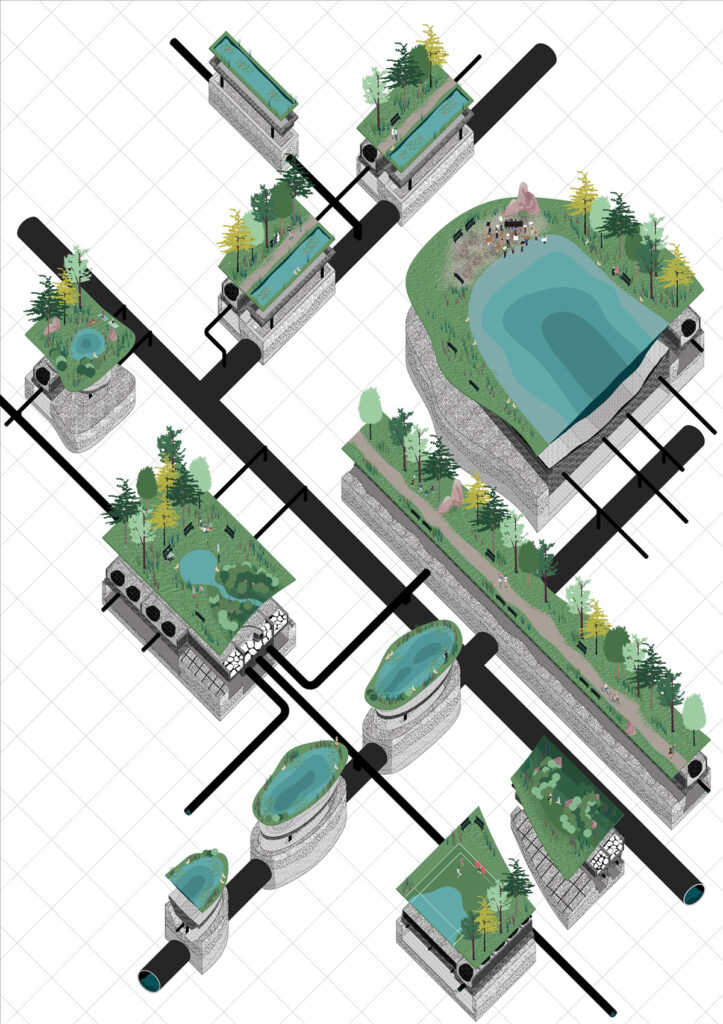

Nature as Public Space

The ideal investigates if nature take on an active role within the urban environment, not only acting as a residual, non-built space, but rather as an integrated system which both interacts with the infrastructural network and acts as public space in which various activities can take place.

Our relationship with nature has always been multi-faceted. Ever since we learned to control aspects of it, becoming less dependent on the various natural cycles, we have tried to find ways of existing with it. This existence has sometimes been a peaceful and collaborative one, but in most historical instances it was driven by the need to control every aspect of our (natural environment).

Our relationship with nature has been an ever present topic within the urban and architectural discourse. How we integrate nature into the built environment, and which functions does nature then take on has been speculated and tested from various viewpoints and has differed significantly depending on the historical period.

Nature has been admired and cherished as the untouchable “other” which was intended only for the purpose of leisure and enjoyment; it has been both functionally and geometrically controlled in order to depict our rule and power over it; nature has been used as a locus of production for various types of goods and materials, often to its (and our) own detriment; we have transported and/or replicated distant and exotic fragments of nature within our dense urban environments, again either for leisure, enjoyment or demonstration of power. Our relationship to nature has always been a simultaneous win and loss.

Today we look towards creating a more integrative and mutually beneficial relationship with nature. By accepting the limited and artificial capacity that “real” nature can obtain within the built environment, we seek for ways in which elements of it can be integrated within our existing systems and networks. Can nature play a double role in the city which results in a win-win situation? Can we provide for nature while enabling it to provide for us as well?